-

MUMORA

-

MUMORA

-

MUMORA

-

MUMORA

From March 12th to June 5th

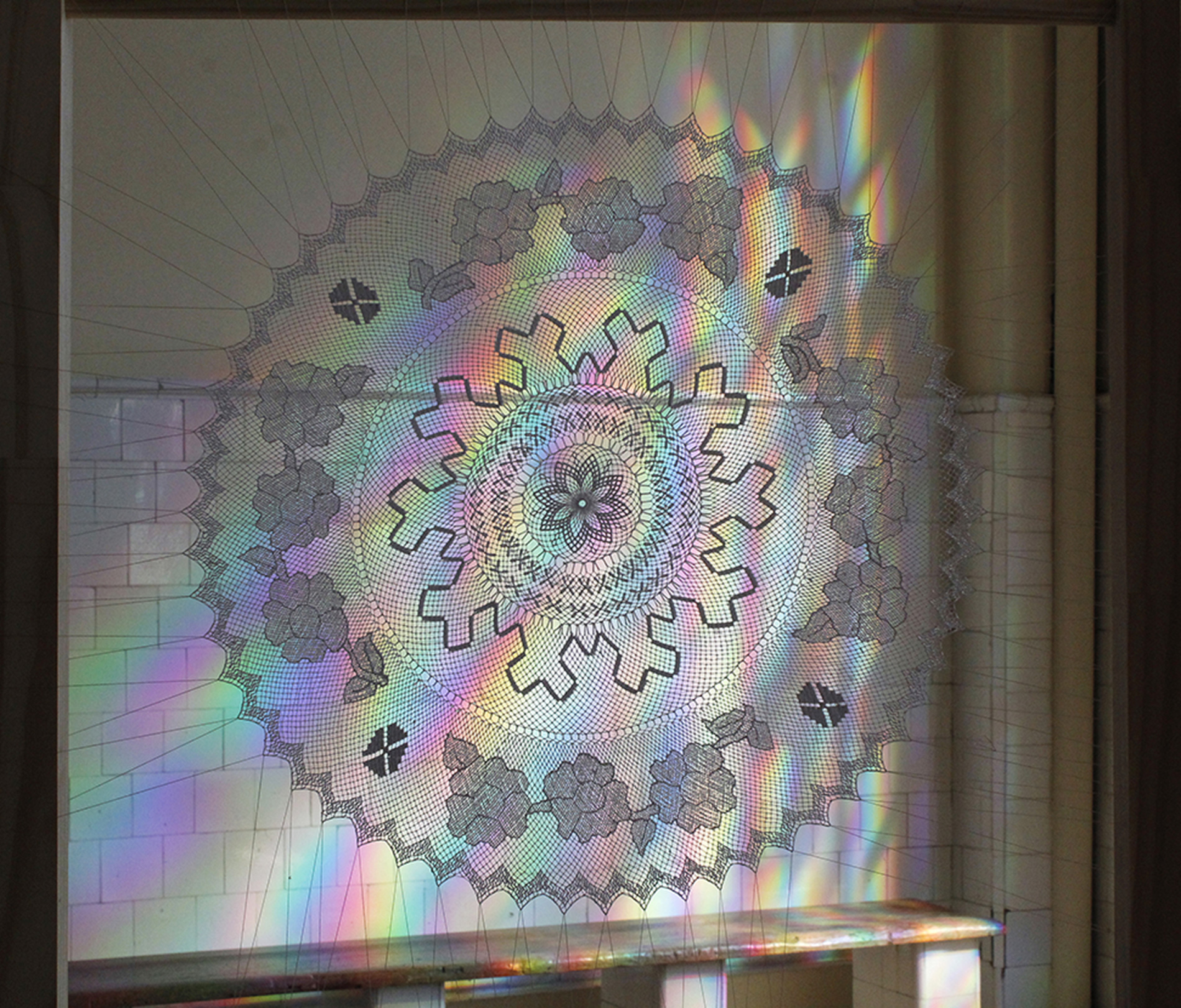

Our Lace Garden

Lace makers: Silvia Amado, Anice Ariza, Magui Ariza, Margarita Ariza, Claudia Aybar, Elva Aybar, Gabriela Belmonte, María Ofelia Belmonte, Tatiana Belmonte, Norma Briseño, Ana Belén Costilla Ariza, Cristina Costilla, Marisel de los Ángeles Costilla, Mirta Costilla, María Laura González, Silvia González, María Magdalena Nuñez, María Marcelina Nuñez, Camila Nieva, Marta Dolores Nuñez, Ely Pacheco, Giselle Paz, Romina Elizabeth Paz, Mayra Robles, Silvia Robles, Agustina Sosa, Elba Sosa, Marcela Sueldo, Anita Toledo, Yohana Torres.

Curatorial work: Alejandra Mizrahi

Curatorial text

Our Lace Garden was inspired by the place where this marvellous lace is still woven today: Tucumán, the Garden of the Republic. The flora in the territory is lush, colourful, and vibrant. Lace makers usually have wonderful blooming gardens, which they look after while simultaneously carrying out their weaving activities. For many of them, planting and tending to the flowers in their gardens is a personal task that fills them with joy and pride. Taking care of their garden and their work is a way of taking care of themselves. Gardens and lace are related, as in many old pieces the lace makers created floral motifs on their meshes. Roses, calla lilies, daisies, busy lizzies, and a myriad of darned motifs can be found in the oldest lace works.

Today the weavers look back at their gardens and bring them to their pieces. Each of them chooses the flowers for different reasons, from emotional matters linked to their genealogies to purely aesthetic motivations that place beauty at the centre of attention.

An article on the Lagartera embroiderers of Toledo mentions the difference between ploughing and embroidery. The text argues that these women are ploughwomen rather than embroiderers. A distinction is made between the act of embroidering, based on a pencil drawing, and that of ploughing, in which work is done on the weft and warp of the fabric, as though ploughing the land, creating patterns out of memory. The difference between embroidering and ploughing is that of following a line marked out a priori versus proposing an unguided furrow. The analogy between working the land and the fabric is highly appropriate for this proposal, in which the lace workers make their lace as if they were gardens. The whole flowery lace work constitutes Our Lace Garden.

Anice Ariza says: “The motif I chose to embroider is a rose. The reason is that among the roses in my garden, which are mostly red, there is a special one that I rescued from my paternal grandmother’s garden that still lives in my garden. This rose represents the presence of my grandmother, forgiveness for my mother who is called Rosa, and love for my two daughters – Ana and Amina – who are my buds. That is why I placed different embroidery stitches inside this rose. It represents a whole, a before and after in my life”.

Mirta Costilla revisits the narrative dimension of the textile and explains how, with this work, people who get involved in the story will not only be able to see beautiful randas but also get to know peculiar aspects of their authors: “I really enjoyed making this lace, which captures my whole childhood, my mother’s house. This flowery embroidery describes the naps of my childhood. I used to enjoy picking the wild fruit called mato and playing with the flowers hanging on the same plant. While I was eating the matos I liked to play with those flowers. They are engraved in my mind. Every time I see those flowers somewhere it is like going back to my childhood. This lace is an opportunity to describe what I felt when I was a child, to capture that, to share what my childhood was like”.

MUMORA is the mobile museum of the randa. It was founded in El Cercado, a rural town in the region of Monteros in the province of Tucumán, with the aim of bringing the textile work of the lace makers to other publics and geographies.

Art historiography has given us imaginary, portable, ephemeral museums, among others. Our itinerant device is part of this genealogy. The Museum has held two exhibitions to date. The first is called Lace Makers’ Autobiographies and was shown at the Museo Nacional de la Historia del Traje, Buenos Aires (2020) and at the Museo Nacional de la Independencia, Tucumán (2021). The second exhibition is called Lace Makers’ Hands Weaving Memories and was presented at the Museo Municipal Sor Josefa Díaz y Clucellas in Santa Fe as part of BIENALSUR (2021).

In these two curatorial works we have worked in a participatory and collective way between the group of lace makers of El Cercado, the artist and researcher Alejandra Mizrahi (from the Universidad Nacional de Tucumán), the anthropologist Lucila Galindez and the historian Isabel Heredia (the latter from the Dirección de Acción Cultural del Ente de Cultura de Tucumán).

On the randa

The randa is a textile. It is a mesh woven and embroidered by a group of women who live in the rural community of El Cercado, Monteros, in the province of Tucumán. Its threads bear witness to a way of being in the world and give a distinctive feature to the community that keeps them alive. As part of the needle lace family, translucent, open, and permeable, the randa knits bodies from various times with different methods through a unique combination of winds, suns, rivers, reed beds and mountains.

The types of randa include table mats on which lamps and vases are placed. Sometimes they are framed with felt and glass as office decorations or become pieces that finish off garments in the form of profuse collars and lace of different thicknesses. Table runners decorate dining rooms.

The ways the randa appears express ways of inhabiting the world. Some of them – far from the place where they originated – resist the mutability of uses and functions. In this resistance, the figures appear to speak to us of an unknown world.

The randa technique was introduced in the Americas during the colonial period. It arrived with the foundation of Ibatín in 1565 and has been woven there for five centuries. The Castilian ladies who settled there brought with them their skills in needle lace making, which they passed on to others. Similar lacework can be seen in Brazil and Paraguay. They all consist of nets or meshes on which motifs are presented. The word “randa” has evolved from a generic term for lace to a technique with characteristic features in different territories.

Lace is one of the oldest forms of human handicraft. They originated in the nets used for hunting and fishing. Over time, they began to be embroidered for decorative purposes. They became very popular in Italy and Spain in the 15th and 16th centuries. They gained popularity as a trend during the 19th century.

The randa is linked to liturgy and folk art. The translation of the fishing net into the miniature of needle lace was used for centuries in ecclesiastical vestments. The whiteness and delicacy of the lace allude to the pure, ceremonial, and mystical origin of a body dignified as a temple of the spirit.

We would like to thank Paulo Vera for the plans and renders.

-

List of works

Silvia Amado

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 53 cm ØAnice Ariza

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 36 x 40 cmMagui Ariza

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 25 cm Ø

Margarita Ariza

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 28 cm ØClaudia Aybar

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 40 x 30 cmElva Aybar

2021. Lace. Cotton thread . 30 cm ØGabriela Belmonte

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 24 cm ØMaría Ofelia Belmonte

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 33 cm ØTatiana Belmonte

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 30 cm ØNorma Briseño

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 24 x 30 cmAna Belén Costilla Ariza

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 21 x 36 cmMarisel de los Ángeles Costilla

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 25 cm ØMirta Costilla

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 30 cm ØCristina Costilla

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 29 cm ØMaría Laura González

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 35 cm ØSilvia González

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 22 x 30 cmCamila Nieva

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 25 x 25 cmMaría Dolores Nuñez

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 29 cm Ø

María Magdalena Nuñez

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 25 cm ØMaría Marcelina Nuñez

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 56 cm ØEly Pacheco

2021. Lace. Cotton thread. 18 cm ØGiselle Paz

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 27 cm ØRomina Elizabeth Paz

2021.Lace. Cotton thread .27 cm ØMayra Robles

2021. Lace. Cotton thread .28 cm ØSilvia Robles

2021.Lace. Cotton thread.77 x 33 cmAgustina Sosa

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 30 cm Ø

Elba Sosa

2021.Lace. Cotton thread.30 cm ØMarcela Sueldo

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 34 cm ØAna María Toledo, Margarita Ariza y Claudia Aybar

Lace (collars, lace, inserts, handkerchief edges and appliqués). Cotton thread. Variable sizesAnita Toledo

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 43 x 43 cm

Yohana Torres

2021.Lace. Cotton thread. 24 x 30 cm -

Works

Venue

Center of Contemporary Art