-

FANTASTIC ZOOLOGY By Pablo La Padula

-

FANTASTIC ZOOLOGY By Pablo La Padula

PRESENTATION

At the MUNTREF Center of Art and Nature, exhibitions of Argentine artist and biologist Pablo La Padula and Peruvian artist Claudia Coca were inaugurated.

The new exhibitions at MUNTREF Center of Art and Nature, Fantastic Zoology by Pablo La Padula, and Claudia Coca’s Don’t say I can’t catch wind, combine science with art, and invite viewers to have a critical look, proper to the scientific world, without evading the social aspect that vindicates the tradition and history of peoples, while highlighting the particular link between humans and nature.

“The relationship of human beings with nature was perhaps the first theme to appear in the history of art. The artistic representation of nature is closely linked to the social perception of the natural world, while artists contribute to a progressive change in the way they relate to it and visualize it,” said rector Aníbal Jozami, director of the Museums of the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero (MUNTREF), during the opening of the event. Pablo La Padula has a great trajectory in the scientific world and Claudia Coca captured in her works the Latin American sense in relation to the rescue of traditions and their conjunction with art,” said Jozami.

The work of La Padula can be seen on the ground floor of the former Tea House El Águila and invites us to reread the historical-cultural marks that reside in the scientific devices and their interpretations, as well as in the decisions that are taken for scientific diffusion, and the forms that these constructions assume in the social imaginary. The materials that are used, the assembly, the lighting and the system of organization, unite to place the spectator in the place of the scientist.

“I don’t care if this show is artistic or scientific. It is a challenge and I want to state with it that art and science are two instruments to know reality and neither is above the other”, said La Padula. In addition, he recalled the importance of the zoo in his career as a place of daily visit during his childhood, a situation that contributed to him studying biological sciences.

The MUNTREF Art and Nature Center, located in the former Buenos Aires zoo – in the process of becoming an Interactive Ecopark – is the fifth museum of the Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero. The building where the mythical El Águila Tea House used to operate was recovered by UNTREF.

Diana Wechsler, director of the Department of Art and Culture and of the UNTREF Specialization and Master in Curatorship in Visual Arts, and curator, together with BenedettaCasini, of both exhibitions, highlighted the importance of having managed to reinvent this space: “We are very happy to have had the chance to occupy this space that, not long ago, was a ruin. We can begin to imagine that from this place other things can be housed and that is part of the challenges that we propose to ourselves and of the challenges that we draw”.

On the other hand, Don’t say I don’t know how to catch the wind, by Peruvian artist Claudia Coca, places the city and all its inhabitants, from humans to animals and plants, on the first floor of this center, in a revisited context. In this project, the words are present, quoting verses from the “indigenous poetry” of the Americas, along with other Latin American voices. The artist, winner of the MUNTREF Center of Art and Nature Residence grant, emphasized the weight of the link that artists establish with society. “Contemporary art is following the path of the construction of thought and knowledge,” she said.

Also present at the inauguration were Peru’s ambassador in Argentina, Peter Camino; Leontina Etchelecu, advisor to the Government of the City of Buenos Aires on Historical Heritage Management; renowned plastic artists Marie Orensanz, Cecilia Catalin, Diana Schufer, Diego Bianchi and, the Iranian, Reza Armarmesh; and art collectors Juan Cambiaso, Sergio Quattrini and Florencio Vals.

“The work of these artists invites us to think along with this space, with these materials, with different points of view and introduces ourselves into the relativity of the gaze, into the possibility of making historical trajectories and putting science and art together. Pablo’s and Claudia’s work are an invitation to become scientists and to realize that these places do not have a single view. You will be scientists with Pablo’s work and naturalists and travellers through Claudia’s critical gaze”, closed Wechsler.

The MUNTREF Art and Nature Center, located at 2725 Sarmiento Avenue in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is open from Wednesday to Sunday from 14:00 to 1:00.

Pablo La Padula: Doctor in Biological Sciences, Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences, University of Buenos Aires. He studied art with Goldenstein, Gorriarena, Stupia, and theorists such as Speranza and Katzenstein at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. His work has been exhibited in institutions such as MALBA, Fundación PROA, Colección Fortabat, Centro Cultural Recoleta, Centro Cultural General San Martín, Palais de Glace, Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas, Casa Nacional del Bicentenario, Centro Cultural Kirchner and in the MUNTREF Centro de Arte Contemporáneo-Premio Braque 2017. His work integrates private collections and that of the Museum of Modern Art of Buenos Aires. He develops an active platform for dialogue between art, science and nature.

-

CURATORIAL TEXT

Pablo La Padula

Fantastic Zoology

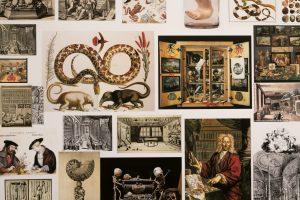

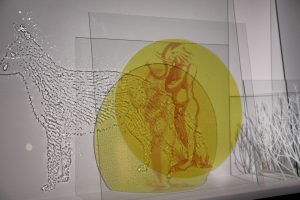

Each space, to be deciphered, requires unique reading keys. The universe of the natural sciences -between the library, the laboratory, the biotherium and the zoo- is the one chosen by Pablo La Padula to test a series of drifts that invite us to reread the historical-cultural marks that reside in the scientific devices and in their interpretations, as well as in the decisions that are taken for the scientific diffusion and the forms that these constructions assume in the imaginary of society. La Padula, the artist, investigates these horizons knowing their order with the purpose of dislocating themt and in this operation, basically aesthetic, to get to open other questions and throw light on unattended aspects to illuminate a fantastic Zoology.

In his words: Fantastic Zoology is visually mounted on the controversy of biological species and its questionable relevance (through the concept of reproductive barrier) as a cultural metaphor that validates the abolition of interpenetrability between different living beings. It thus forgets that in biological diversity and its great gene flow underlies the power of development and adaptability of life in the face of the new. And it is through mutual support (Piotr Kropotkin, 1890-96) between the different, precisely, that life opens its way and guarantees the great harmonic chain of beings; this idea is questioned by the imperialist metaphor of survival of the strongest or fittest (Charles Darwin, 1859).

On that beautiful pure and crystalline lens, which Victorian positivist science consolidated in a true and definitive way of seeing, Fantastic Zoology proposes its mistiness through an operation of visual confusion. In order to do so, it uses a museography of the taxonomic order of words and things (sic: Michel Foucault, 1966), taking as a variable the use of the image as an anachronistic tractioner in the construction of modes of seeing (sic: John Berger, 1972).

Fantastic zoology starts from the singularities of the fabulous Aristotelian pipe dreams of Pliny the Elder and their future sifting to a modern concept of a normalized species as a corpuscle or atom that floats inert and solitary in a Newtonian space lacking any reference or hierarchy. And it reaches its explanatory edge, in which the uncertainty principle and the quantum of the beginning of the twentieth century projected a molecular and transgenetic biology of species, in which everything revolves generatively and, in temporal hyperbole, places us on the dawn of thought about the living and its ineffable definition and classification. From this generative chaos, and evolutionary obsolescence, Fantastic Zoology seeks refuge and redemption in a polysemic and horizontal device as they were and are the cabinets of transdisciplinary biological wonders of all times.

With diverse resources, some coming from the laboratory, others from the collection of materials from nature and others from the scientific imagination and literature, La Padula builds what takes the form of a large installation -integrated by several zones that are read as part of a system and in relation to it. Its materials meet with a logic of assembly, lighting and a system of organisation that places the spectator in the disturbing place of the one who has to decipher the hidden keys between the pieces. He puts him virtually in the scientist’s place, proposing to him some reading hypothesis that will allow him to enter this singular world, between art and science, between matter and imagination.

Diana B. Wechsler

Curator